In the course of several years of research, I have come across many interesting drawings and photos of the ubiquitous Army horse. We can learn a little about how the military felt about its animals through the art it produced institutionally and by individual soldiers.

In the Army, cavalry soldiers, teamsters, farriers and the pack-master all had to develop relationships with the military's standard beasts of burden, the horse, donkey and mule. Individual soldier's feelings towards their equine comrades varied, from hatred, to ambivalence, to love and even friendship.

|

This sketch (left) from 1864, which is actually quite good and reveals the artist's fondness for his subject, was found on on paper pasted to the the reverse of a Civil War soldier's discharge certificate.

The Army had many animals in its care over the course of it's history, perhaps hundreds of thousands of horses, donkeys and mules served in the military. Naturally, the Army issued thousands of orders related to the care, grooming and feeding of the creatures and veterinary surgeons were regularly employed. At one time or another, all the arms of service (Artillery, Cavalry, and Infantry) utilized them.

One of the primary uses was as a pack-animal, a four legged cargadore. The Army used horses and mules for this purpose, although mules were preferred for their rugged hardiness over swifter horses. As early as the 1850's there were written instructions on how to properly assemble the cargo, or packs, on the animal's back; complete with drawings.

|

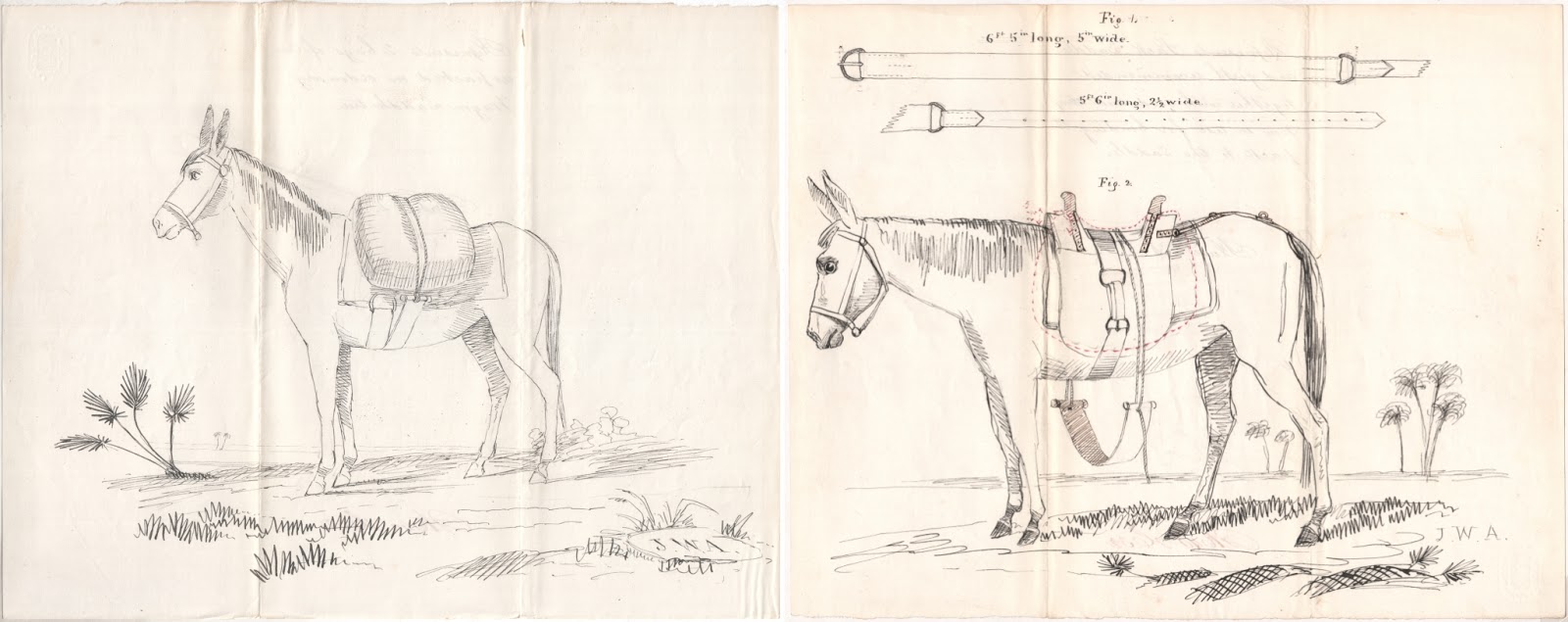

Some officers, sufficiently motivated, also tried to come up with solutions to the many problems associated with having the animals carrying heavy loads, including cannon barrels and ammunition chests. The two sketches (above) were drawn by an officer of the Quartermaster's Department while stationed in Florida in 1857. He was trying to devise a new system of pack arrangement that did not injure the animal's back.

Some officers, sufficiently motivated, also tried to come up with solutions to the many problems associated with having the animals carrying heavy loads, including cannon barrels and ammunition chests. The two sketches (above) were drawn by an officer of the Quartermaster's Department while stationed in Florida in 1857. He was trying to devise a new system of pack arrangement that did not injure the animal's back.

The photo (left) shows a typical pack arrangement , circa 1890, with the following essential articles : (1) boards, (2) saddle & pads, (3) cinch, (4) corona, (5) blanket, (6) blind, (7) pad for gun, etc., (8) sling rope, (9) lash rope.

This picture (right), from the same series, shows a typically beleaguered mule who had been packed to transport a small cannon, or more likely, a Gatling Gun. The soldier's fur hat and impressively large fur mittens, indicate this mule was serving in a cold climate. The picture also clearly shows how securing the packs, boxes and other equipment required a complex system of cordage and binding with straps and rope to make certain the material sat correctly to distribute weight, did not injure the animal, and would not fall off if the animal brushed against rocks or tree limbs, or bolted.

This image (left) purports to show the first American horses to arrive on Luzon that were brought in Dewey's fleet. The Army was so enamored of its own horses or afraid the native horses in the Philippines were not strong enough, that it took its own mounts to the Islands in 1898. It was eventually discovered that horses don't fare very well on long ocean voyages, and the Army switched to using the smaller, yet fleet, native ponies. Horses as pack-animals were in great need, and every command had a contingent of military packers and civilians, as well as a corral and stables. One smart commander, Colonel John Stotsenberg (1st Nebraska Vol Inf) even arranged to have the Army's premier pack-master, Chris Gilson, sent to Manila to instruct the other packers.

In 1910 the Army decided to keep a file on each of it's horses, in the same manner that it did for soldiers, who were all supposed to be photographed, finger-printed and properly described for identification purposes after 1906. The photo (right) shows the proper type of image that was needed. Luckily, the regulations did not order the men to take the horse's hoof-prints, but it did mandate photo-identification of each animal. Complex instructions were issued on how to photograph the horse, the position of the animal, even what kind of lighting and lens to use. The diagram (below) shows just how a system was supposed to work, assuming the animal would hold still and pose properly.

A series of test photos of the Horse Identification System, 1910 (below).

Sources : RG94, entry 409, file coan243eb1864; RG92, entry 225, box 776; RG111, entry 44, box 350; RG111rb, box 10.