This amazing document from the Committee of Revolutionary Claims from the House of Representatives (rg233, hr25a-g20.1), is a recruiting poster from Massachusetts dated April 1761, asking for men to serve the Crown in the provincial (colonial) troops for a tour of duty. Although pre-dating the Revolution by nearly fourteen years, it clearly shows the precedents set down in the British system of recruiting and enlistment that were used in the United States Army during the Revolution until the time of the Civil War.

It sets the basic standards used for the recruitment, enlistment and mustering of so-called 'volunteers', a category of soldier relatively unique to the Anglo-American military model. Volunteers were neither militia, nor regulars, but faced all the hazards and duty of regulars when in service. The primary difference, legally, was the term of service which was generally much shorter for volunteers who were usually called out to deal with some immediate military threat.

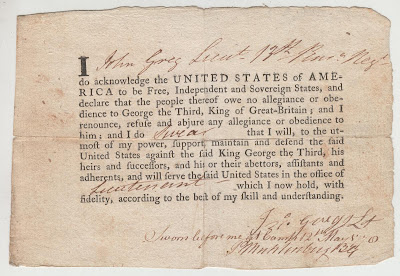

|

| RG233, hr25a-g20.1, Colonial Recruiting Poster, Massachusetts Bay, 1761 |

This record specifically shows the type of men to be enlisted: not too young, not too old, infirm or 'negro'. This ugly precedent, which allowed none save one African per company as a servant to the Captain, was adopted and incorporated into the regulations of the American Army until after World War Two. It also set two unfortunate and costly precedents that plagued our government for decades; that of the 'bounty' or cash payment, supplemental to the monthly salary, for faithful service; and the worst element, limited terms of service. This document clearly states that the men enlisted would be discharged no later than July 1762, or sooner if the 'Regulars' returned or the threat dissolved.

During the Revolutionary War, the threat of short-term service, coupled with promises of bounty money that the Continental establishment could not afford, almost scuttled the entire war for the Americans. Only by enlisting men for the duration of the war, which turned out to be eight years, did the Continental Army ever achieve any cohesiveness. There is no doubt that militia and volunteers have given valuable, heroic service, but the threat of the dreaded 'expiration of term of service' which legally required the muster-out of volunteers by a certain, fixed date, regardless of the exigencies of the war, has cost the military more than has probably been estimated.

This document is a great example of the traditions our military inherited from precedents set down by the British Colonies. This was the only system that many of the colonists who became Patriots understood, and they were comfortable and willing to deal with it's disadvantages, for the advantage it gave them in retaining their liberty and freedom from compulsory military service.